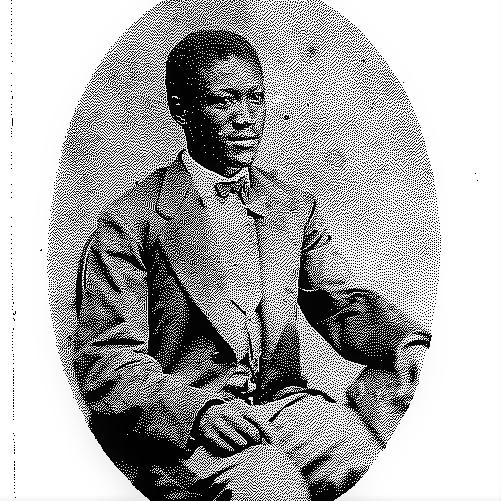

Photo courtesy of Gerald Karwowski

Margo Drummond’s “Peter D. Thomas: A Racinian to Remember,” Belle City Magazine, February 11, 2019,

Photo credit: Gerald Karwowski

In 1886, the Wisconsin State Democratic Convention was held in Union Grove. At that gathering a 39-year-old former slave named Peter D. Thomas was nominated to serve as Racine County Coroner. Due to spelling errors on several ballots cast for Thomas the election hung in doubt. A recount determined that the votes in question had indeed been cast for Thomas, making him the first African-American county officer ever elected in the state of Wisconsin.

He had come a long way from his time in bondage on a 1,000-acre plantation in northern Tennessee where he was born on April 8, 1847. Nurtured on a diet of clabbered milk, cornbread and hog fat, Peter relied upon his mother to provide him with a single pair of pants made of stiff duck material, his clothing being described as “not much.”

Before he was old enough to do field work, Thomas served as an errand boy, a house boy, and a stable boy. He was also entrusted with accompanying the four daughters who occupied the “big house” when they went riding with prospective suitors. It was Thomas’ job to discern how interested (or not) the young ladies were in their companions. A “yes” signaled him to fall back, a “no” to stick close by.

When war broke out Thomas, along with half of the eligible slaves from surrounding plantations, was sent to Island #10 in the Mississippi River where the Confederates hoped to blockade the river. The attempt failed and in 1862 the Union Army took possession of the island. It was then that 15-year-old Thomas became the “batman” or servant to Lieutenant Charles B. Nelson of Company G, Fifteenth Wisconsin Infantry, assigned to care for Nelson’s tent, carry his sword and revolver when not in battle and to perform whatever other tasks required.

Due to injuries incurred in the Battle of New Hope Church, Lt. Nelson returned to his home in Beloit, taking Thomas with him. While doing farm work, Thomas was asked why he didn’t enlist himself. His reply was, “I tried but they won’t take me.” But later on, take him they did. Having enlisted in August of 1864 in the 18th U.S. Colored Troops, Thomas participated in the battles of Franklin and Nashville in the state where he had once been a slave. He was mustered out in 1865.

Thomas returned to Beloit where he graduated from high school and completed one year at Beloit College, hoping to earn a teaching degree that he could use to teach people of color in the South. His dreams were shattered by the recognition that southern whites would not allow people of color to be educated, especially by a fellow African-American. So it was that Thomas moved on to Chicago where he was employed as a brandy tester. During his four years in that capacity he proved himself able to identify any brand of liquor without the label, meanwhile never succumbing to addiction.

In 1883, Thomas came to Racine where he first lived at 1208 Villa and later, with his wife, Carrie, at their cottage at 1119 Center Street. He became well known and highly regarded by his fellow citizens who described him as “a man of economy and thrift” who has “more friends among Racine’s businessmen than any other member of his race.” Having worked as a custodian at the First National Bank and the Racine County Courthouse, Thomas also remained active in the Governor Harvey Post No. l7, Grand Army of the Republic, for which he served one term as Junior Vice Commander, as a delegate of his Post to the State Encampment, and as a representative to several meetings of the National Organization. As chairman of the headstone committee, he took charge of laying out a Civil War plot at Historic Mound Cemetery where 12 of his Union comrades, including nurse Hattie Stewart Harrington are buried.

During his two-year tenure as Racine County Coroner, Peter Thomas held 31 inquests investigating the deaths of four women, nine men, one girl and five boys. Causes of death included three suicides, one murder, four drownings and four cases listed as “married.”

On December ll, 1925, Thomas died at his home on Center Street of accidental asphyxiation by gas, believed to have been caused by a faulty furnace pipe. He was buried in a Grand Army of the Republic steel vault at Mound Cemetery, not far from the Civil War burial plot that he had once overseen.

Margo Drummond’s interest in local history began when she became involved with Preservation Racine. For 31 years, she taught high school courses on Racine History and Death and Dying, Issues of Living and Life. She wrote two books, “Blessings of Being Mortal: How a Mature Understanding of Death Can Free Us to Live Wisely and Well” and “Here’s to Your Health.”